We’ve been blogging for free. If you enjoy our content, consider supporting us!

Vista Land & Lifescapes (VLL) has always been a story of two engines: the cyclical churn of homebuilding and condo turnovers on one side, and the steadier cadence of rental income from commercial assets on the other. In the first nine months of 2025, both engines did their job—barely. Consolidated revenues rose a modest 2.2% to ₱28.399 billion, supported by real estate sales (+~3%) and rental income (+~3%).

But the quarter’s real headline isn’t the topline. It’s the bill that arrives after the sales and rent checks clear: financing cost.

A decent earnings print—until you look at the interest line

VLL reported net income of ₱9.462 billion, up ~4.3% year-on-year (9M 2024: ₱9.076 billion), with EPS rising to ₱0.668 (from ₱0.627).

On paper, that’s a clean, incremental improvement—especially in a market that’s still juggling buyer affordability, selective demand, and uneven project completion cycles.

Yet under the surface, the company’s progress is being increasingly “taxed” by the cost of money. Interest and other financing charges jumped ~17% to ₱5.925 billion (from ₱5.043 billion), with management attributing the increase primarily to lower capitalization of interest during the period—meaning more borrowing costs flowed directly to the income statement rather than being parked in asset costs.

The financial soundness table tells the same story in a single ratio: EBITDA-to-total interest fell to 1.34x (from 1.89x a year earlier). That is not a crisis number, but it is a clear signal that interest burden is rising faster than operating cushion.

Operating discipline helped—but it can’t fully outrun higher carry

To VLL’s credit, the company did what businesses do when the interest meter runs fast: tighten the controllables. Operating expenses fell to ₱7.057 billion from ₱7.742 billion, supported by lower advertising and promotion, professional fees, and repairs and maintenance, per management’s discussion.

Costs of real estate sales also edged down to ₱4.552 billion from ₱4.625 billion.

This discipline is exactly why net income still grew. But it also highlights the key constraint: there is a limit to how far expense efficiency can go when financing costs are moving in the opposite direction. Eventually, the financing line starts dictating what kind of growth is “allowed”—how fast you can launch, how aggressively you can build investment properties, and how quickly you can recycle capital into new inventory.

The balance sheet says “stable,” but leverage keeps the interest sensitivity high

As of September 30, 2025, VLL’s total assets rose to ₱387.581 billion (from ₱377.939 billion at end-2024), while total liabilities stayed broadly flat at ₱242.599 billion (vs ₱241.852 billion). Equity improved to ₱144.982 billion (from ₱136.087 billion), reflecting the period’s earnings.

Liquidity remained adequate but slightly softer: current ratio of 1.74x, down from 1.81x at end-2024.

Meanwhile, VLL disclosed leverage measures such as debt-to-equity at ~1.10x and net debt-to-equity at ~0.84x as of period-end.

The debt stack remains meaningful: notes payable at ₱104.240 billion, bank loans at ₱54.653 billion, and loans payable at ₱11.442 billion, plus lease liabilities.

VLL also described refinancing actions—most notably, loans payable fell ~41% as borrowings were refinanced into bank loans.

This matters because when financing costs are the pressure point, debt mix changes—what’s fixed, what reprices, what can be prepaid—become as important as unit sales and mall occupancy.

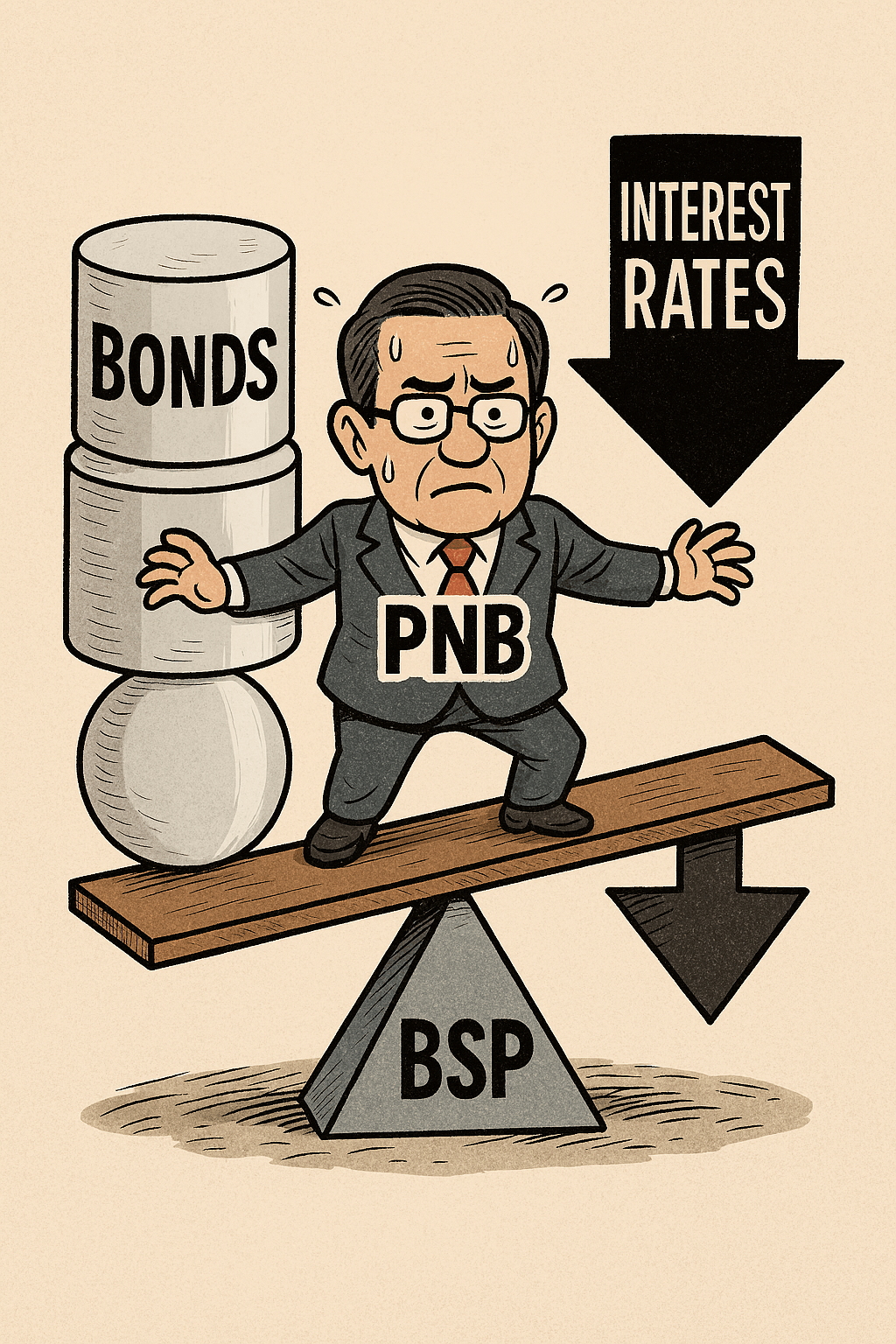

The Macro Catalyst: BSP rate cuts and the refinancing window

BSP has already moved—rates are down, and the cycle may be near its end

The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) has delivered a meaningful easing cycle. In its December 11, 2025 decision, the BSP cut the policy (overnight RRP) rate by 25 bps to 4.50%, with the deposit and lending facility rates correspondingly adjusted. Reports also noted that the BSP has reduced rates by a cumulative ~200 bps since the easing cycle began (August 2024) and signaled that the easing cycle is “nearing its end” and future moves would be data-dependent.

Earlier in 2025, the BSP also cut rates to 5.25% in June (another 25 bps), reinforcing the broader downtrend in domestic benchmark rates.

How does this help VLL? It depends on what portion of debt can actually reprice

A BSP rate cut is not a magic eraser for interest expense—especially for issuers with large chunks of fixed-rate bonds and notes. VLL itself discloses that much of its interest-bearing liabilities carry fixed rates, including notes payable with coupons across a wide band and peso bank loans with fixed rates in a mid-to-high single-digit range.

Still, rate cuts matter in three practical ways:

- Cheaper refinancing of maturing peso obligations

As policy rates fall, banks typically reprice new loans and rollovers lower (though not one-for-one). For a developer with ongoing maturities and refinancing activity, the real benefit arrives when old tranches are replaced with new ones at lower coupons. VLL’s own disclosures show continued funding activity and covenant monitoring, and it even noted a new ₱5 billion, three-year loan facility signed for refinancing purposes after the reporting period—suggesting refinancing remains an active playbook, not a theoretical one. - Improved negotiating leverage with lenders

In a lower-rate environment, issuers with scale and bank relationships can re-open conversations on pricing, tenor, and covenant headroom. VLL highlights compliance with key covenants (current ratio, leverage, DSCR-type measures) across its debt programs, which supports lender confidence and can translate into better refinancing terms. - A slower growth penalty from interest carry

The most immediate “earnings” impact is not always a dramatic reduction in interest expense; it can be a reduction in the incremental cost of funding new launches and capex. This matters for VLL because investment properties and project launches expanded during the period—investment properties rose to ₱145.524 billion and inventories to ₱61.692 billion—both of which typically have funding footprints. Lower benchmark rates can soften the future carrying-cost curve.

The fine print: what BSP cuts won’t fix

Two realities temper the optimism:

- Fixed-rate debt doesn’t reprice unless it is refinanced early, called, or replaced at maturity—sometimes with redemption premiums and transaction costs. VLL’s disclosure includes multiple note and bond programs with specified terms and redemption features, implying refinancing benefits arrive unevenly across maturities.

- USD debt costs are influenced more by global dollar rates and FX than by BSP alone. VLL has significant USD-denominated notes payable exposure and also holds USD investments, which means refinancing economics must consider both rate differentials and currency movements.

Bottom line: VLL’s operating story is intact—its financing story is the swing factor

VLL’s 9M 2025 results read like a company doing the right operational things: steadying revenues through rentals, managing costs, and keeping earnings modestly higher.

But the same report makes it clear where the market should keep its flashlight trained: ₱5.925 billion of financing charges and an interest-coverage indicator that has weakened year-on-year.

If the BSP’s easing cycle has indeed brought policy rates down to 4.50% and created a window for cheaper refinancing, VLL has a clear incentive to use it—especially with refinancing activity already evident and a new ₱5 billion facility signed for that purpose.

In short: VLL can still sell homes and collect rents, but the next chapter may be written by the treasurer as much as by the sales team. In an environment where the BSP has cut rates and signaled the easing cycle may be nearing its end, execution on refinancing—timing, pricing, and maturity management—could be the difference between steady profits and squeezed returns.

We’ve been blogging for free. If you enjoy our content, consider supporting us!